Category: STORIES WITHIN THE STORY

IRS Gives Refund Check to Man for Paying Too Much, While Claiming to the Court He Avoided Paying Taxes

- April 7, 2020

- admin

- No Comments

This is the second in a series of articles focusing on the false conviction of Michael Quiel.

By Ron Lee

US~Observer

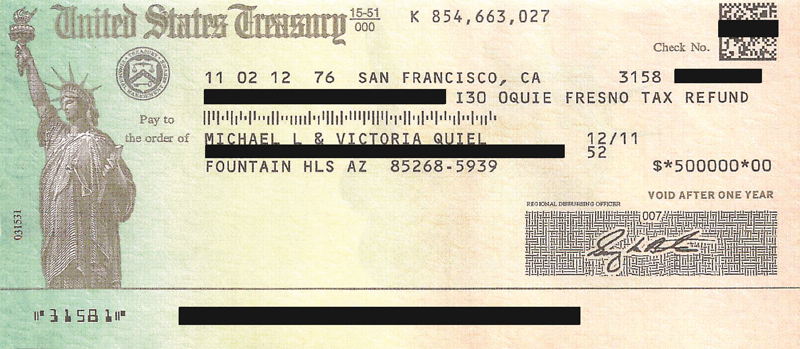

In 2012, Michael Quiel was already fighting for his freedom and his very life against the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Department of Justice’s (DOJ) false allegations that he had tried to hide assets offshore to avoid taxes. The sum of those alleged assets should have generated large tax liabilities – meaning he’d owe a lot in taxes. As such he was advised by his attorney Michael Minns to pay the IRS $500,000.00, just in case they found he owed taxes. He immediately paid the IRS. What happened next shows the truth of the matter.

As mentioned in our previous article, throughout Michael Quiel’s 2013 trial the federal prosecutor and witnesses ran rampant, waging an all-out war on Quiel by committing fraud on the court. In fact, as we will uncover in this series of short articles relating to Michael Quiel’s false prosecution and subsequent conviction, the entire government’s case was built around a fraudulent hypothesis. This supposition only worked if they could have the truly guilty party, Michael Quiel’s former tax attorney Christopher Rusch, portray that Quiel as the orchestrator in a conspiracy to defraud the United States government of tax revenue. The only problem was that all the facts showed something far different.

Seven months after sending the IRS the $500,000 payment, Michael Quiel received a check back from the IRS and a special notice. It wasn’t until the closing arguments of Quiel’s 2013 trial that those two items were brought to the jury’s attention by Quiel’s attorney Michael Minns.

Minns revealed that Quiel had received a complete refund of what he had paid – all $500,000.00 of it. Not only that, he read a letter from the IRS stating that in addition to the refund check, due to business losses, Quiel had a $1.4 million credit with the government which could apply to past or future tax years.

From Michael Quiel’s book, Rigged, “So the supposed ‘victim’ in this case—the U.S. Treasury—in fact owed me over a million dollars. Minns went on to explain that a person can be held criminally liable in a tax case only if it can be clearly shown that he or she willfully intended to do wrong.” Owing nothing clearly shows Michael Quiel had no reason to do anything wrong.

It leaves one wondering how he could have been prosecuted in the first place, let alone convicted of anything.

In our next look at Quiel’s wrongful conviction we’ll show the political reasons for his prosecution, and the need for a guilty verdict. Let’s just say, not all Clinton bodies wind up cold, some just get burned at the altar of “justice.”

Quiel’s book, Rigged – due out soon – does an excellent job of outlining the entire case, that is still going on to this day. All profits from the sale of his book will be donated to benefit innocent victims of false charges and prosecution. Michael Quiel is adamant that he help as many people as he can from ever having to go through the same type of abuse he endured at the hands of prosecutors who turn a blind eye to truth and justice.

Update 2 – Judge Tielborg ignored two recent Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) opinions

- April 1, 2020

- admin

- No Comments

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES (SCOTUS)

-

-

-

Court ignores SCOTUS new Opinions” Court allows imposters to represent Government and ignores two recent Supreme Court cases and issues false opinion and then orders that Quiel CAN NOT APPEAL.

-

By disregarding SCOTUS opinion NRLB vs SW General and accepting Teilborg opinion then you allow “Acting” Officers to exceed the 210 days permitted and thus hold a permanent position without “Senate Confirmation”.

-

By accepting Teilborg opinion, then visiting “Russian probe”…Mueller’s appointment as an “inferior officer” by Rosenstein as “Heads of Department” is legal as an “inferior officer”. Constitution, Article 2, Sec 2, Claus 2 reads …”the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.” Inferior officer is not Senate Confirmed.

-

By accepting Teilborg opinion you allow the “Senate Confirmation” process to be aborted and leave “Officers of the United States” to be appointed for life time terms by the President or Head of Departments without Senate Confirmation. (Decided March 2017)

-

-

-

-

-

If you disregard SCOTUS opinion Lucia vs SEC and accept Teilborg opinion, then visiting “Russian probe”…Mueller’s appointment as an “inferior officer” by Rosenstein as “Heads of Department” is legal as an “inferior officer”. Constitution, Article 2, Sec 2, Claus 2 reads …”the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.”

-

Teilborg opinion gives Mueller gets LIFE TIME appointment even though he has NOT been confirmed by the Senate. The only life time appoint is given to Federal Judges but must have “Senate Confirmation”.

-

In summary Mueller as an inferior officer, if Rosenstein is removed from his appointed position, on his own, becomes his own boss and can operate without supervision until a time he deems necessary. This is a life time appointment only given to Federal Judges that must be appointed and confirmed by the Senate. (Decided June 2018)

-

-

DOJ and IRS publish Quiel family members social security numbers on the internet and cause identity theft.

- March 27, 2020

- admin

- No Comments

With the digital age, identity theft has become one of the biggest threats to our financial and personal lives. Laws, at both the federal and state level, are continually being passed to protect our personal information and punish those who release it without our consent. Yet at least one government agency fails to take such protections seriously.

At the federal level, according to its Rules of Civil Procedure, filings made with courts of law must be redacted including omitting Social Security numbers (SSNs), taxpayer IDs, and birthdates. But when a government agency fails to follow this statute, it suffers no consequences. Meanwhile, private citizens and businesses do not benefit from such immunity and are subject to prosecution and fines.

In the case of Michael Quiel, target of an IRS indictment and later found innocent on most charges as chronicled in his new book, Rigged, he fell victim to this blatant double standard. During Christmas time in 2012, Quiel received a call from a family member saying he had found the Quiel family’s SSNs posted on online. They evidently had been retrieved from the evidence file located on the US District Court’s filing system, PACER—Public Access to Court Electronic Records.

Quiel immediately looked up his case on various internet sites. To his surprise, he found his tax returns posted online, along with the SSNs of each member of his family, including him, his wife, and their three young daughters. The six years of tax returns were part of the five hundred thousand pages of documents submitted by the IRS in its indictment against him.

According to the law, Quiel’s tax returns were allowed to be on the PACER site because of the IRS lawsuit. But by failing to redact all SSNs, the IRS violated federal statutes intended to protect the identity of its taxpayers. Concerned about the consequences of the IRS’s blunder, Quiel phoned his attorney, Michael Minns, who assured his client he would contact the prosecutor handling the case Monica Edlestein. He also said he would address the IRS’s negligence in court. Quiel’s trial with the IRS was set for March 5, 2013.

In the meantime, Quiel took the protective measure of enrolling his entire family on LifeLock, which is an online service that protects customers against identity theft. Through Lifelock, Quiel was notified that his thirteen-year-old daughter had fallen victim to identity fraud—someone had applied for credit using her name shortly after her Social Security number had been posted.

Quiel then used Google to identify sites that had posted his tax returns. Third parties that follow court cases often republish PACER data on their sites. He let each one know that his tax returns contained confidential information that violated federal rules. To Quiel’s relief, every single site he contacted immediately took his tax returns down demonstrating how seriously they took legal compliance.

In contrast, the IRS took a cavalier attitude to protecting citizens’ SSNs. During Quiel’s trial, Minns informed the judge of the IRS’s malfeasance. Monica Edelstein told the court that the Social Security numbers had now been redacted. But, in reality, that had happened only after the IRS first published the unredacted tax returns and left those online for months. Unfortunately, by the time the agency fixed its mistake, his family members’ identities had already been compromised.

“The double standard is clear as day. There simply isn’t any accountability when the government does something wrong,” says Michael Quiel. “If I, as a private individual or business owner, released the Social Security numbers of IRS employees and their family members, I’d likely be on the hook for big fines, lawsuits, and most probably prison.” In the end, the IRS got away with at best its incompetence and at worst negligent intent without any consequence from the legal system. Meanwhile, the SSNs of all five members of Quiel’s family will be forever at risk.

TEILBORG OPINION AND IRS COVERUP

- March 23, 2020

- admin

- No Comments

-

IRS Master File was requested multiple times by Quiel at trial. This would have contained the FBAR’s for 2000-03 or lack thereof.

-

After the numerous attempts to obtain Quiel’s IRS IMF, Quiel learned from an IRS agent that the criminal investigations unit in Phoenix was holding his file.

-

Judge Teilborg denied Quiel access to his IMF file from the IRS. Teilborg ruled on August 16, 2013, “Quiel claims that the Court should have refused to admit redacted documents that the defense was unable to review….. the Court notes that Quiel objected to the admission of IRS Form 4340 and sought that the entire IMF file be disclosed at trial. This objection was overruled…”

-

Judge Teilborg ruled on September 28, 2018 , “the court will not reconsider its prior finding that Petitioner procedurally defaulted this claim, because “it involves information that (Petitioner) could have learned with reasonable diligence prior to appeal.”

-

Judge Teilborg acknowledges in his first order in 2013 that Quiel sought the entire IMF file be disclosed at trial but contradicts himself in the next order in 2018, stating it could have been learned prior to appeal.

Related Stories

Michael Quiel’s recent triumph regarding the financial interest issue will exonerate him from his wrongful conviction in 2013!!

Innocence Amid Government Conspiracy

Civil Attorneys Butler, Hubbert and Uhalde Become Co-Conspirators

Becoming a Judge by Convicting the Innocent?

IRS Relies on Fraudulent Evidence to Collect Fines and Taxes

Chris Rusch aka Christian Reeves Continues Crimes

FOX NEWS STORY

IRS Gives Refund Check to Man for Paying Too Much, While Claiming to the Court He Avoided Paying Taxes

Clinton “Killing Machine” Destroyed Phoenix Man

Attorney Turned IRS Informant

Attorney Rusch turns on clients, Gov’t fails to prove tax due

CLINTON TIES TO UBS

Update 2 – Judge Tielborg ignored two recent Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) opinions

DOJ and IRS publish Quiel family members social security numbers on the internet and cause identity theft.

Fraud on the Court Through Prosecutorial Misconduct